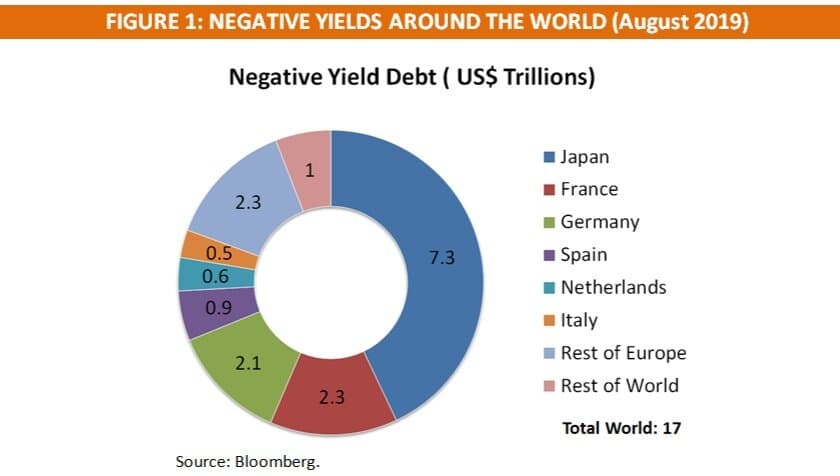

As of August 2019, there was over US$17 trillion in debt with negative yields (i.e. interest rates) around the world1, most of it in Europe and Japan (see figure 1). To put this in perspective, $17 trillion is around 20% of the entire global debt market! Negative-yield debt is unprecedented in modern financial history and can be a difficult concept to comprehend because with negative yields, a purchaser of debt is guaranteed to lose money if he or she holds the investment until its maturity. If this is the case, why would anyone buy debt with a negative yield and how did we get to the point where negative-yield debt is so widespread worldwide? And could negative yields arise in the United States at some point in time?

The background for negative yields is the low interest rate environment we are currently living in around the world. Largely due to long-term structural factors, including the aging of the global population, excess global savings, the impact of technology and the spread of globalization, inflation has been very low in recent years relative to what has been the historical norm. In Europe and Japan, for example, core inflation is currently around 1% and 0.5% per annum, respectively (historically, an annual core inflation rate of around 2% or higher would have been considered normal). Inflation and interest rates are directly linked and, as a result, low inflation has contributed to low interest rates throughout much of the developed world2.

Many believe that inflation will remain persistently low in the coming years and some even believe that parts of the developed world will experience deflation (negative inflation). Expectations of deflation in particular could partly explain why negative-yielding debt has grown recently because in a deflationary environment, an investment in debt with negative yields could actually be attractive3. So, low yields in the world in general and the expectation or fear of deflation in the future are one part of the story behind negative yields.

The main part of the story, however, is the role of central banks around the world. Starting with the European Central Bank in 2014, several international central banks, including those in Japan, Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark, have turned to negative interest rates in what can be deemed an experimental monetary policy approach. Facing stubbornly low growth and inflation, and with the policy rate in their countries already at or close to zero, central banks in Europe and Japan simply had run out of many of the traditional tools used by central banks to stimulate economic activity. As a result, they turned to negative interest rates in the hope that a new approach could produce better results.

The primary way in which central banks around the world have implemented negative rates is by establishing a negative deposit rate. The deposit rate is the interest rate that commercial banks receive for the excess reserves they hold at the central bank4. Currently, the European Central Bank (ECB) has set a deposit rate of -0.5%. So today commercial banks in the countries of the European Union effectively have to pay the central bank for their (excess) reserves. This rather strange situation sheds some light on the question of why anyone would purchase negative-yield debt: some market players (in this case, commercial banks in Europe and Japan) are required to accept negative yields as a result of the decisions of monetary authorities5.

Once central banks set a negative deposit rate, negative yields began to be transmitted to other parts of the debt market. This is because most interest rates in an economy are linked to several key benchmark rates, one of which is the aforementioned deposit rate. So in countries with a negative deposit rate, it was natural that negative yields could and would expand to other parts of the fixed income universe. The linkage between interest rates in an economy thus helps to explain why negative yields have become so widespread in Europe and Japan.

What can we say about negative yields as a monetary policy decision five years after the start of this experiment? Unfortunately, there is limited evidence that the policy as a whole has been successful as both economic growth and inflation in both Europe and Japan have not shown any significant improvement in recent years6. Also, it is not clear that negative rates have led to a marked increase in lending by banks. Conversely, negative rates have hurt financial institutions as the profitability of banks suffers when interest rates are very low (or negative). Broadly speaking, even though central banks in Europe and Japan seem committed to pursuing negative rates as a policy, it is fair to say that there is a great degree of skepticism in the market about the effectiveness of this approach. In addition, some believe that other policy approaches, such as looser fiscal policy (i.e. increased government spending), could be more successful.

Finally, what about the possibility of negative yields in the United States? In our view, the probability of this is fairly low for the time being. Economic growth in the US is structurally higher than it is in Europe and Japan and both inflation and interest rates remain well above those in most of the rest of the developed world. We believe this set of conditions makes negative rates much more unlikely in the United States. However, even if the US is able to avoid negative interest rates, it is not immune from the structural factors leading to low yields throughout the world. We have already seen a marked decline in US interest rates in recent years and we believe low yields in the US are likely to persist for some time. While today’s low yield environment presents many challenges for investors and especially for savers, it is nevertheless the reality of the current investment landscape.

[1] Ainger, John. “The Unstoppable Surge in Negative Yields Reaches $17 Trillion.” Bloomberg. 30 August 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/negative-yield-bonds/.

[2] With low inflation, the nominal yield that investors demand when purchasing fixed income securities is commensurately lower. See endnote number 3 below for a further explanation of nominal yields.

[3] An investor in fixed income typically looks at both the nominal (or stated) yield of the bond and the real yield, the nominal yield less the expected rate of inflation. The real yield is arguably more important for the investor. In a normal inflationary scenario, with let’s stay expected inflation of 2%, an investor in a bond with a stated yield of 3% would anticipate earning a nominal yield of 3% but a real yield of 1% (nominal yield less the expected rate of inflation). Under a deflationary scenario, the mathematical calculation is the same but can lead to a surprising result. With an expected rate of deflation of 2% (or one could say inflation of -2%), an investor in a bond with a stated yield of -1% would anticipate earning a nominal yield of -1% but a real yield of 1% (-1% -(-2%)).

[4] In excess of the reserves they are required to keep at the central bank for regulatory purposes.

[5] There are other institutions that are also directly or indirectly required to accept negative yields. One example that comes to mind is pension funds. Pension funds typically invest a substantial amount of their investment portfolio in high-quality fixed income securities in their home markets. In countries like Germany or Japan many of these investments have negative yields today. So in the course of following their normal investment approach, pension funds in these countries effectively have to accept negative yields in portions of their portfolios today.

[6] Of course it is difficult to say whether economic conditions would have been even worse in the absence of negative rates.