In this edition of Capital Insight Partners’ Investment Perspectives, we discuss the topic of concentrated stock positions, which occur when a significant percentage of an investor’s wealth is tied to a single stock. Concentrated stock positions create substantial risk for investors and often lead to meaningfully lower wealth over the long-run compared to a well-diversified stock portfolio. As such, we believe that selling a concentrated stock position is generally the best alternative for most investors, particularly those with a long time horizon.

A concentrated stock (or equity) position occurs when a significant percentage of an investor’s wealth is tied to a single stock. Typically an investment that accounts for around 10% or more of an investor’s total portfolio would be considered a concentrated position1. Investors can acquire concentrated equity positions as a result of different circumstances. Among the most common are: 1) inheritance, 2) executive compensation, 3) the sale of a business and 4) substantial price appreciation of a single investment relative to the rest of an investor’s portfolio.

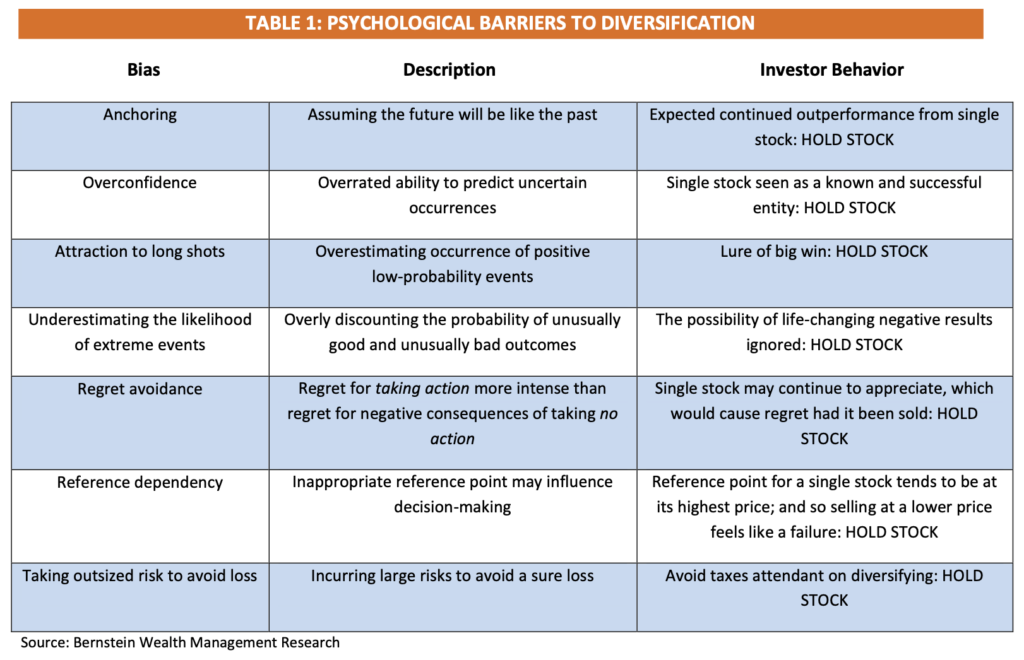

Once an investor acquires a concentrated position, there is a tendency to hold on to it. For one thing, many investors are reluctant to sell the investment due to the capital gains taxes that may result from the sale, which can be substantial. Numerous behavioral biases also make it difficult for many investors to sell concentrated positions. Table 1 below highlights many of these behavioral biases.

Beyond behavioral factors and taxes, many investors simply do not fully appreciate the significant risks associated with concentrated stock positions. On the one hand, concentrated stock positions are substantially more volatile than diversified portfolios, thus creating a much higher level of risk. For example, according to the investment consulting firm Cambridge Associates, during the ten year period ending June 30, 2013, the volatility of the median stock in the S&P 500 index was nearly 70% greater than that of the index2. This type of excessive volatility is very challenging for most investors to deal with and typically leads to suboptimal investment decisions over time.

What is often less well understood, however, is that concentrated stock positions typically underperform diversified stock portfolios over the long-term, often by a wide margin. For example, Bernstein Wealth Management compared the returns of the S&P 500 index between 1984 and 2003 to the returns of the individual stocks in the index during this same time period. The findings were dramatic. Whereas the S&P 500 index generated an average annual return of 13.0% from 1984 to 2003, the average stock3 in the index generated an average annual return of only 10.3%, or 2.7 percentage points less per year. Clearly some stocks outperformed the S&P 500 index during these twenty years, but many stocks underperformed it, often by a very wide margin. The result was that the average stock in the S&P 500 substantially underperformed the index.

Sometimes it is easy to think of the winning stocks in the market. In recent years, higher-growth technology stocks, such as Google, Facebook, Apple and Amazon, would come to mind. However, it can be easy to forget that for every winning stock in the market, there is often a loser. And, furthermore, that many losing stocks can decline significantly in value over long periods of time. In the previously cited study, Cambridge Associates found that 55 components of the S&P 500 declined by over 50% in value over the ten year period ending June 30, 20134.

While there are great potential rewards for being concentrated in the right stock, the costs for being concentrated in the wrong stock can be significantly greater.

Taxes and Concentrated Stock Positions

Taxes are an important consideration when discussing concentrated stock positions. This is because many of these investments have significant capital gains tax liabilities embedded in them as a result of substantial price appreciation over the course of many years. Reluctance to realizing capital gains can be a powerful deterrent against selling concentrated stock positions. However, what many investors fail to fully appreciate is that the benefits of better diversifying their portfolios can easily offset the upfront taxes that would be incurred.

We have designed a hypothetical scenario to illustrate this point. Assume an investor has a concentrated stock position with a current market value of $1 million. The cost basis in the stock is $250,000, which means that the embedded capital gains tax liability is $750,000 (i.e. the stock was purchased at a value of $250,000 and has subsequently increased in value by $750,000 to its current value of $1 million). If we assume a 20% capital gains tax rate, the investor would have to pay $150,000 in taxes ($750,000 in capital gains times the 20% tax rate) if he or she sold the investment.

Given this significant upfront cost, does it make sense to sell the holding? In most cases, the answer is yes, particularly for investors with a longer-term time horizon. The reason is simple: over time, a well-diversified stock portfolio generally outperforms the average single stock by a large enough amount to comfortably offset the upfront capital gains tax payment.

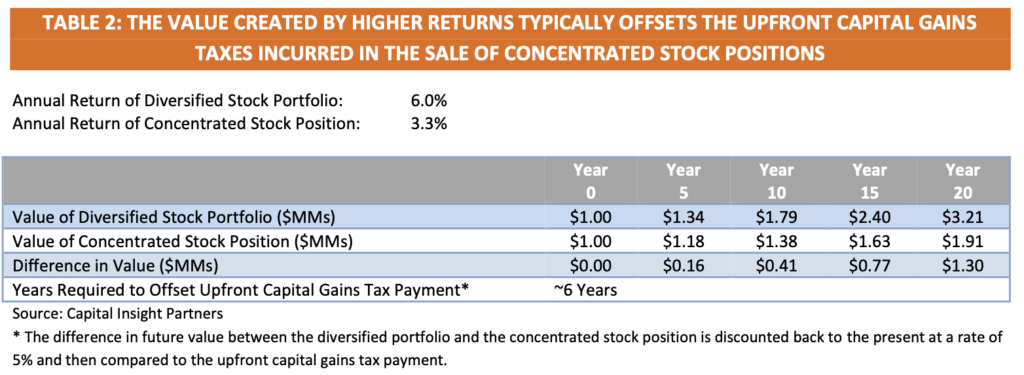

To quantify this, let’s return to our hypothetical example. Assume the investor sells his or her $1 million position and invests the proceeds in a diversified stock portfolio. We will assume that this stock portfolio earns a return of 6% per year going forward, which we believe is a realistic assumption based on our firm’s long-term capital market expectations. In contrast, we will assume that the concentrated stock position earns a return of 3.3% going forward. Why 3.3%? You might recall that the key finding of the Bernstein Wealth Management study was that the average single stock underperformed the diversified portfolio (specifically in this case the S&P 500 index) by 2.7 percentage points per year over a twenty year period. So in our hypothetical example, 2.7 percentage points less per year than 6% is 3.3%. What is the difference in future wealth between earning 6% per year and 3.3% per year?

Investment Policy Statement

As highlighted in table 2, the higher returns of the diversified stock portfolio generate significantly greater wealth over time. The $1 million investment in the diversified portfolio grows to $1.79 million in 10 years and $3.21 million in 20 years. In contrast, the concentrated stock position only grows to $1.38 million in 10 years and $1.91 million in 20 years. In other words, the investment in the diversified stock portfolio leads to an extra $410,000 in wealth over 10 years and an extra $1.3 million in wealth over 20 years! The greater wealth created by investing in the diversified portfolio easily offsets the initial capital gains tax payment; in fact, it only takes about 6 years to completely offset the tax cost. For any investor with a long-term time horizon, this modest 6-year payback period would be considered highly attractive5.

Even if we were to assume that the concentrated stock position did significantly better than a return of 3.3%, it would still make sense to sell it in most cases. For example, let’s assume that the concentrated stock position earned a return of 4.7% going forward versus a return of 6% for the diversified stock portfolio (in other words, we now assume that the concentrated stock position only underperforms by 1.3 percentage points per year). In this scenario, the diversified portfolio would lead to an extra $210,000 in wealth over 10 years and an extra $730,000 in wealth over 20 years! It would now take the diversified stock portfolio about 11 years to offset the initial capital gains tax payment, which would still be considered highly attractive for most investors with a long-term time horizon.

And the following point is worth repeating: irrespective of return considerations, by selling a concentrated position an investor is significantly reducing risk.

Staged Sale of a Concentrated Stock Position

Although there is a compelling rationale for selling a concentrated stock position immediately (and investing the proceeds in a diversified stock portfolio), many investors may have difficulty making such a significant change to their portfolio at once. This could be due to behavioral reasons or other considerations. For these investors, a strategy of disposing of the concentrated stock position over several years can be a good solution. Proceeding in this more gradual manner can help many investors become more comfortable with the idea of selling a concentrated stock position and can make it possible to overcome initial reluctance to taking action. In our view, for this strategy to be most effective it is very important that the sale occur over a reasonably short period of time (we generally recommend no more than 3 to 5 years) and that a substantial amount of concentrated stock is sold early in the staged sale timeline. In this way, a meaningful portion of the risk associated with the concentrated stock position is eliminated early on.

Alternatives to Selling a Concentrated Stock Position

While selling a concentrated stock position, either immediately or over a defined period of time, is typically the best solution for most investors, there are several other potential alternatives. These include: making charitable gifts, hedging through the use of derivatives, hedging through the use of exchange-traded shares or sector funds and, finally, participating in an exchange fund6. We will briefly discuss two of these strategies: charitable gifts and hedging through derivatives.

Gifting appreciated concentrated stock to tax-exempt charitable organizations can be a very attractive solution for investors who are charitably inclined. The main financial benefit of this strategy is that the investor is typically able to gift the full appreciated value of the investment while avoiding capital gains taxes. In addition, the individual making the contribution may be able to generate an immediate tax deduction, although this benefit is now not as widely available as a result of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. While donating shares directly to a specific charitable entity is a very common way to fund charitable goals, other options include donating shares to a private foundation, donating shares to a donor-advised fund and creating charitable remainder or charitable lead trusts7.

Hedging a concentrated stock position through derivative strategies may be appropriate for certain investors. Specifically, executives or other individuals who may be restricted from selling their shares may find hedging strategies appealing. There are numerous types of hedging strategies, including protective puts, covered calls, zero-premium collars and prepaid variable forward sales8. The downside of derivative hedging strategies is that they tend to be complex and can be expensive. Therefore, hedging strategies may not be appropriate for all investors.

In Conclusion

Due to strong behavioral biases and the reluctance to incur capital gains taxes, many investors tend to hold on to concentrated stock positions once they have been acquired. Unfortunately, in doing so, investors usually reduce the long-term expected returns of their portfolio while taking on a much higher than necessary level of risk. By selling a concentrated stock position and investing the proceeds in a diversified stock portfolio, most investors will generate substantially greater wealth over time. The extra wealth created will often comfortably outweigh any capital gains taxes that are incurred. For certain investors for whom selling a concentrated stock position is not feasible or appropriate, there are a few other potential solutions, including donating the shares to charitable organizations. Speaking with an investment advisor with experience in managing concentrated stock positions can help investors better assess the different alternatives and find an appropriate solution tailored to their specific circumstance.

ENDNOTES

1 The threshold for what constitutes a concentrated stock position can be subjective and may vary across different investors depending on their particular financial circumstances. While 10% is a commonly-used threshold, in certain cases a much lower threshold could be appropriate. Separately, it is important to analyze concentrations in investor portfolios across other dimensions as well, including an investor’s exposure to industry sectors. For example, let’s assume an investor owns 5 stocks in the telecommunications sector and that each of these investments accounts for 5% of the investor’s total portfolio. While each individual position is well below the 10% concentrated stock position threshold, in the aggregate the investor’s exposure to the telecommunications sector is extremely high at 25%. In our view, an excessive level of concentration of this type in one industry sector would represent a significant risk to the investor’s portfolio and would require reducing the size of each individual investment to well below 5% in this example (assuming all the investments were kept in the portfolio).

2 Cambridge Associates. “Concentrated Stock Portfolios.” September 2013.

3 In its study, Bernstein defined average stock as a stock with average volatility. Stocks with above average volatility actually underperformed the index by even a larger margin during the period evaluated by Bernstein.

4 Cambridge Associates. “Concentrated Stock Portfolios.” September 2013.

5 It is worth highlighting that in our exercise we assumed a fairly high level of embedded capital gains taxes in the stock position ($750,000 in unrealized gains compared to its $1 million value). While this level of embedded gains is not unusual in these situations, it should be noted that for concentrated stock positions with lower levels of embedded capital gains taxes, the rationale for selling the position becomes even more compelling.

6 Vanguard. “Investment Solutions and Alternatives for Addressing Concentrated Equity.” 2007

7 Cambridge Associates. “Concentrated Stock Portfolios.” September 2013.

8 William Blair. “Managing Concentrated Equity Risk through Strategic Diversifications.” August 2017

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bernstein Wealth Management Research. “The Enviable Dilemma – Concentrated Stock: Hold, Sell, or Hedge.” March 2004.

Cambridge Associates. “Concentrated Stock Portfolios.” September 2013.

Keebler, Robert. “Tax/Financial Planning for Concentrated, Low-Basis Stock Positions.” Taxes-The Tax Magazine (October 2011): 5-8.

Robert W. Baird & Co. “The Hidden Cost of Holding a Concentrated Stock Position. Why diversification can help to protect wealth.” 2016.

Vanguard. “Investment Solutions and Alternatives for Addressing Concentrated Equity.” 2007. William Blair. “Managing Concentrated Equity Risk through Strategic Diversifications.” August 2017.